Abstract

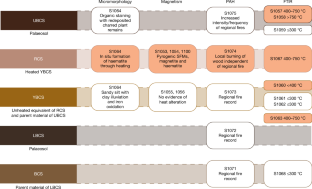

Fire-making is a uniquely human innovation that stands apart from other complex behaviours such as tool production, symbolic culture and social communication. Controlled fire use provided adaptive opportunities that had profound effects on human evolution. Benefits included warmth, protection from predators, cooking and creation of illuminated spaces that became focal points for social interaction1,2,3. Fire use developed over a million years, progressing from harvesting natural fire to maintaining and ultimately making fire4. However, determining when and how fire use evolved is challenging because natural and anthropogenic burning are hard to distinguish5,6,7. Although geochemical methods have improved interpretations of heated deposits, unequivocal evidence of deliberate fire-making has remained elusive. Here we present evidence of fire-making on a 400,000-year-old buried landsurface at Barnham (UK), where heated sediments and fire-cracked flint handaxes were found alongside two fragments of iron pyrite—a mineral used in later periods to strike sparks with flint. Geological studies show that pyrite is locally rare, suggesting it was brought deliberately to the site for fire-making. The emergence of this technological capability provided important social and adaptive benefits, including the ability to cook food on demand—particularly meat—thereby enhancing digestibility and energy availability, which may have been crucial for hominin brain evolution3.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

27,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

39,95 €

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data is presented in the Supplementary Information or is linked to Excel spreadsheets.

References

Perles, C. La Prehistoire du Feu (Masson, 1977).

Roebroeks, W. & Villa, P. On the earliest evidence for habitual use of fire in Europe. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 5209–5214 (2011).

Wrangham, R. Control of fire in the Paleolithic: evaluating the cooking hypothesis. Curr. Anthrop. 58, S303–S313 (2017).

Gowlett J. A. J. in Sur le chemin de l’humanité. Via humanitatis: les grandes étapes de l’évolution morphologique et culturelle de l’Homme: émergence de l’être humain (ed. de Lumley, H.) 171–197 (Académie Pontificale des Sciences/CNRS, 2015).

James, S. R. Hominid use of fire in the Lower and Middle Pleistocene: s review of the evidence. Curr. Anthropol. 30, 1–26 (1989).

Sandgathe, D. M. et al. Timing of the appearance of habitual fire use. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, E298 (2011).

Goldberg, P., Miller, C. E. & Mentzer, S. M. Recognizing fire in the Paleolithic archaeological record. Curr. Anthrop. 58, S175–S190 (2017).

Gowlett, J. A. J. et al. Early archaeological sites, hominid remains and traces of fire from Chesowanja, Kenya. Nature 294, 125–129 (1981).

Bellomo, R. V. Methods of determining early hominid behavioural activities associated with the controlled use of fire at FxJj 20 Main, Koobi Fora, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 27, 173–195 (1994).

Hlubik, S. et al. Researching the Nature of fire at 1.5 Mya on the site of FxJj20 AB, Koobi Fora, Kenya, using high-resolution spatial analysis and FTIR spectrometry. Curr. Anthrop. 58, S243–S257 (2017).

Brain, C. K. & Sillen, A. Evidence from the Swartkrans cave for the earliest use of fire. Nature 336, 464–466 (1988).

Berna, F. et al. Microstratigraphic evidence of in situ fire in the Acheulean strata of Wonderwerk Cave, Northern Cape province, South Africa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, E1215–E1220 (2012).

Alperson-Afil, N., Richter, D. & Goren-Inbar, N. Phantom hearths and the use of fire at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, Israel. PaleoAnthrop. 2007, 1–15 (2007).

Chazan, M. Toward a long prehistory of Fire. Curr. Anthrop. 58, S351–S359 (2017).

Sorensen, A. C. On the relationship between climate and Neandertal fire use during the Last Glacial in south-west France. Quat. Int. 436A, 114–128 (2017).

Ravon, A.-L. in Crossing the Human Threshold. Dynamic Transformation and Persistent Places during the Middle Pleistocene (eds Pope, M. et al.) 106–122 (Routledge, 2018).

Sanz, M. et al. Early evidence of fire in south-western Europe: the Acheulean site of Gruta da Aroeira (Torres Novas, Portugal). Sci. Rep. 10, 12053 (2020).

de Lumley, H. Terra Amata, Nice, Alpes-Maritimes, France, Tome V: Comportement et Mode de Vie des Chasseurs Acheuléens de Terra Amata (Editions CNRS, 2016).

Ollé, A. et al. The Middle Pleistocene site of La Cansaladeta (Tarragona, Spain): stratigraphic and archaeological succession. Quat. Int. 393, 137–157 (2016).

Stepanchuk, V. N. & Moigne, A.-M. MIS 11-locality of Medzhibozh, Ukraine: Archaeological and paleozoological evidence. Quat. Int. 409, 241–254 (2016).

Gowlett, J. A. J. et al. Beeches Pit – archaeology, assemblage dynamics and early fire history of a Middle Pleistocene site in East Anglia, UK. Eurasian Prehist. 3, 3–38 (2005).

Sorensen, A. C., Claude, E. & Soressi, M. Neandertal fire-making technology inferred from microwear analysis. Sci. Rep. 8, 10065 (2018).

Ashton, N. M., Lewis, S. G. & Parfitt, S. A. Excavations at Barnham, Suffolk, 1989-94 (British Museum, 1998).

Ashton, N. M. et al. Handaxe and non-handaxe assemblages during Marine Isotope Stage 11 in northern Europe: Recent investigations at Barnham, Suffolk, UK. J. Quat. Sci. 31, 837–843 (2016).

Preece, R. C. & Penkman, K. E. H. New faunal analyses and amino acid dating of the Lower Palaeolithic site at East Farm, Barnham, Suffolk. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 116, 363–377 (2005).

Voinchet, P. et al. New chronological data (ESR and ESR/U-series) for the earliest Acheulean sites of northwestern Europe. J. Quat. Sci. 30, 610–622 (2015).

Brittingham, A. et al. Geochemical evidence for the control of fire by Middle Palaeolithic hominins. Sci. Rep. 9, 15368 (2019).

Denis, E. H. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in lake sediments record historic fire events: validation using HPLC-fluorescence detection. Org. Geochem. 45, 7–17 (2012).

Hough, W. Fire-making Apparatus in the United States National Museum (United States Government Printing Office, 1928); https://archive.org/details/firemakingappara0000walt.

Stapert, D. & Johansen, L. Flint and pyrite: making fire in the Stone Age. Antiq. 73, 765–777 (1999).

Sorensen, A. C., Roebroeks, W. & Van Gijn, A.-L. Fire production in the deep past: the expedient strike-a-light model. J. Archaeol. Sci. 42, 476–486 (2014).

Jeans, C. V., Turchyn, A. V. & Hu, X.-F. Sulfur isotope patterns of iron sulfide and barite nodules in the Upper Cretaceous Chalk of England and their regional significance in the origin of coloured chalks. Acta Geologica Polonica 66, 227–256 (2016).

Bristow, C. R. 1990. Geology of the Country around Bury St Edmunds. Memoir British Geological Survey, Sheet 189 (England and Wales) (British Geological Survey, 1990).

Ander, E. L. et al. Baseline Report Series 13: The Great Ouse Chalk aquifer, East Anglia. Commissioned Report CR/04/236N (British Geological Survey, 2004).

Preece, R. C. et al. Terrestrial environments during MIS 11: evidence from the Palaeolithic site at West Stow, Suffolk, UK. Quat. Sci. Rev. 26, 1236–1300 (2007).

Wiessner, P. W. Embers of society: Firelight talk among the Ju/‘hoansi Bushmen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 14027–14035 (2014).

Gingerich, P. D. Pattern and rate in the Plio-Pleistocene evolution of modern human brain size. Sci. Rep. 12, 11216 (2022).

Dunbar, R. I. M. The social brain hypothesis. Evol. Anthrop. 6, 178–190 (1998).

Villa, P. & Lenoir, M. in The Evolution of Hominin Diets (eds Hublin, J-J. & Richards, M. P.) 59–85 (Springer, 2009).

Locht, J.-L. et al. Une occupation de la phase ancienne du Paléolithique moyen à Therdonne (Oise): chronostratigraphie, production de pointes Levallois et réduction des nucleus. Gallia Préhistoire 52, 1–32 (2010).

Malinsky-Buller, A. The muddle in the Middle Pleistocene: the Lower–Middle Paleolithic transition from the Levantine perspective. J. World Prehist. 29, 1–78 (2016).

Rots, V. Insights into early Middle Palaeolithic tool use and hafting in Western Europe. The functional analysis of level {IIa} of the early Middle Palaeolithic site of Biache-Saint-Vaast (France). J. Archaeol. Sci. 40, 497–506 (2013).

Mazza, P. et al. A new Palaeolithic discovery: tar-hafted stone tools in a European Mid-Pleistocene bone-bearing bed. J. Archaeol. Sci. 33, 1310–1318 (2006).

Parfitt, S. A. & Bello, S. M. Bone tools, carnivore chewing and heavy percussion: assessing conflicting interpretations of Lower and Upper Palaeolithic bone assemblages. R. Soc. Open Sci. 11, 231163 (2024).

Milks, A. et al. A double-pointed wooden throwing stick from Schöningen, Germany: results and new insights from a multianalytical study. PLoS ONE 18, e0287719 (2023).

Mentzer, S. M. Microarchaeological approaches to the identification and interpretation of combustion features in prehistoric archaeological sites. J. Archaeol. Meth. Theory 21, 616–668 (2014).

Barbetti, M. Traces of fire in the archaeological record, before one million years ago? J. Hum. Evol. 15, 771–781 (1986).

Thieme, H. in The Hominid Individual in Context: Archaeological Investigations of Lower and Middle Palaeolithic Landscapes, Locales and Artefacts (eds Gamble, C. & Porr, M.) 115–132 (Routledge, 2005).

Stahlschmidt, M. C. et al. On the evidence for human use and control of fire at Schöningen. J. Hum. Evol. 89, 181–201 (2015).

Stoops, G. Guidelines for Analysis and Description of Soil and Regolith Thin Sections (Soil Science Society of America, 2003).

Stoops, G. Guidelines for Analysis and Description of Soil and Regolith Thin Sections (Wiley, 2021).

Herries, A. I. & Fisher, E. C. Multidimensional GIS modelling of magnetic mineralogy as a proxy for fire use and spatial patterning: evidence from the Middle Stone Age bearing sea cave of Pinnacle Point 13B (Western Cape, South Africa). J. Hum. Evol. 59, 306–320 (2010).

Herrejón Lagunilla, Á et al. An experimental approach to the preservation potential of magnetic signatures in anthropogenic fires. PLoS ONE 14, e0221592 (2019).

Oldfield, F. & Crowther, J. Establishing fire incidence in temperate soils using magnetic measurements. Palaeogeog. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 249, 362–369 (2007).

Gedye, S. J. et al. The use of mineral magnetism in the reconstruction of fire history: a case study from Lago di Origlio, Swiss Alps. Palaeogeog. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 164, 101–110 (2000).

Dearing, J. A. in Environmental Magnetism: a Practical Guide (eds Walden, J. et al.) 25–62 (Quaternary Research Association, 1999).

Maher, B. A. The magnetic properties of some synthetic submicron magnetites. Geophys. J. R. Astron. Soc. 94, 83–96 (1988).

Maki, D., Homburg, J. A. & Brosowske, S. D. Thermally activated mineralogical transformations in archaeological hearths: inversion from maghemite γFe2O4 phase to haematite αFe2O4 form. Archaeolog. Prospec. 13, 207–227 (2006).

Liu, Q. et al. Environmental magnetism: principles and applications. Rev. Geophys. 50, 2–50 (2012).

Thompson, R. & Oldfield, F. Environmental Magnetism (Allen and Unwin, 1986).

Linford, N. T. & Canti, M. G. Geophysical evidence for fires in antiquity: preliminary results from an experimental study. Paper given at the EGS XXIV General Assembly in The Hague, April 1999. Archaeol. Prospec. 8, 211–225 (2001).

Ketterings, Q. M., Bigham, J. M. & Laperche, V. Changes in soil mineralogy and texture caused by slash-and-burn fires in Sumatra, Indonesia. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 64, 1108–1117 (2000).

Pulley, S., Lagesse, J. & Ellery, W. The mineral magnetic signatures of fire in the Kromrivier wetland, South Africa. J. Soils Sed. 17, 1170–1181 (2017).

Walden, J., Oldfield, F. & Smith, J. P. (eds) Environmental Magnetism: a Practical Guide (Quaternary Research Association, 1999).

Worm, H. U. On the superparamagnetic–stable single domain transition for magnetite, and frequency dependence of susceptibility. Geophys. J. Int. 133, 201–206 (1988).

Blundell, A. et al. Controlling factors for the spatial variability of soil magnetic susceptibility across England and Wales. Earth Sci. Rev. 95, 158–188 (2009).

Snape, L. & Church, M. J. in Wild Things 2.0: Further Advances in Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Research (eds Walker, J. & Clinnick, D.) 55–80 (Oxbow Books, 2019).

Karp, A. T. et al. Fire distinguishers: refined interpretations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons for paleo-applications. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 289, 93–113 (2020).

Song, Y. et al. Distribution of pyrolytic PAHs across the Triassic–Jurassic boundary in the Sichuan Basin, southwestern China: evidence of wildfire outside the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province. Earth Sci. Rev. 201, 102970 (2020).

Hytönen, K. et al. Gas–particle distribution of PAHs in wood combustion emission determined with annular denuders, filter, and polyurethane foam adsorbent. Aerosol Sci. Tech. 43, 442–454 (2009).

McDonald, J. D. et al. Fine particle and gaseous emission rates from residential wood combustion. Environ. Sci. Tech. 34, 2080–2091 (2000).

Hoare, S. Assessing the function of Palaeolithic hearths: experiments on intensity of luminosity and radiative heat outputs from different fuel sources. J. Paleol. Archaeol. 3, 537–565 (2020).

Argiriadis, E. et al. Lake sediment fecal and biomass burning biomarkers provide direct evidence for prehistoric human-lit fires in New Zealand. Sci. Rep. 8, 12113 (2018).

Campos, I. & Abrantes, N. Forest fires as drivers of contamination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to the terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 24, 100293 (2021).

Sojinu, O. S., Sonibare, O. O. & Zeng, E. Y. Concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils of a mangrove forest affected by forest fire. Toxicolog. Environ. Chem. 93, 450–461 (2011).

Yunker, M. B. et al. PAHs in the Fraser River basin: a critical appraisal of PAH ratios as indicators of PAH source and composition. Org. Geochem. 33, 489–515 (2002).

Faboya, O. L. et al. Impact of forest fires on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon concentrations and stable carbon isotope compositions in burnt soils from tropical forest, Nigeria. Sci. Afr. 8, e00331 (2020).

Weiner, S. Microarchaeology-Beyond the Visible Archaeological Record (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010).

Madejova, J. & Komadel, P. Baseline studies of the Clay Mineral Society source clays: infrared methods. Clays Clay Min. 49, 410–432 (2001).

Berna, F. et al. Sediments exposed to high temperatures: reconstructing pyrotechnological processes in Late Bronze and Iron Age strata at Tel dor (Israel). J. Archaeol. Sci. 34, 358–373 (2007).

Saikia, B. J. & Parthasarathy, G. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic characterization of kaolinite from Assam and Meghalaya, Northeastern India. J. Mod. Phys. 1, 206–210 (2010).

Bridgland, D. R. Clast Lithological Analysis. Technical Guide No. 3 (Quaternary Research Association, 1986).

Gale, S. J. & Hoare, P. G. Quaternary Sediments: Petrographic Methods for the Study of Unlithified Rocks (Blackburn, 2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank M. Stahlschmidt for the analysis and interpretation of initial work on the micromorphology and invaluable assistance to S.H. on the additional thin sections. We are grateful to C. Jeans and W. Lord for discussions on the pyrite. We also thank C. Williams for help with the illustrations. Access to the site on the Euston Estate has been provided by the Duke of Grafton and the Heading family, and we are grateful to M. Hawthorne, D. Heading, E. Heading and R. Heading for their ready assistance throughout the fieldwork. Further logistical support has been provided by D. Switzer of PR International. We thank the excavation and post-excavation teams, in particular L. Dale, X. Ding, S. Hunter, D. Jones, I. Klipsch, M. Özturan, A. Rawlinson and I. Taylor, and site manager T. B. Jones. The research was supported by the Calleva Foundation through the Pathways to Ancient Britain project and for S.M.B. through the Human Prehistoric Behaviour in 3D project, and the paper is a contribution to the Natural History Museum’s Evolution of Life research theme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.D., N.A., S.M.B., M.H., S.H., S.G.L., J.M., J.N., S.O.’C., S.A.P., A.S. and C.S. wrote the paper. R.D., N.A. and C.L. analysed the artefacts. M.L. and S.P. were responsible for palynology. S.H. performed micromorphology and environmental magnetism experiments, and analysed PAHs. M.H. performed FTIR spectroscopy. S.M.B., J.N., S.A.P. and A.S. analysed pyrites. S.G.L. and N.A. performed lithological analyses. J.M. performed photogrammetry and photography.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Susan Mentzer, Ségolène Vandevelde and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

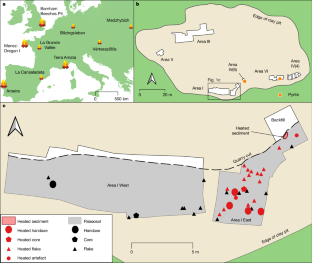

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Geology of Barnham.

a. Map of the Breckland area showing sites of Barnham, Beeches Pit and Devereux’s Pit. Also shown is the boundary of the Lower and Middle Chalk and key superficial deposits discussed in the text. b. Schematic cross-section of the sedimentary sequence at East Farm Barnham, showing locations of samples for dating, biostratigraphy, palynology and contexts containing archaeology. Units 1–3 = glacial sediments; unit 4 = lag gravel; unit 5 = lacustrine sediments with lateral transition between unit 5c in the middle of the basin and unit 5e on the edge; unit 6 = palaeosol; unit 7 = brickearth. Credits: Panel a contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v.3.0 (British Geological Survey UKRI, 2025). Panel b created by C. Williams.

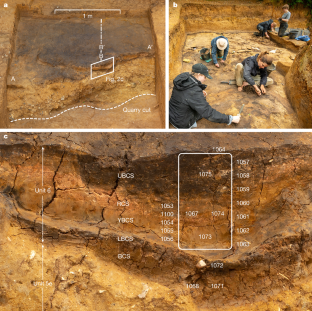

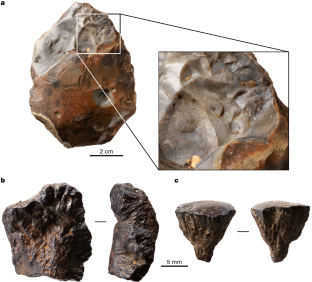

Extended Data Fig. 2 Heat shattered handaxes from Barnham.

a. Central part of heat-shattered handaxe with 25 refitting pieces excavated from within a small zone (35 cm across) in Area I East. b. Top part of heat-shattered handaxe from Area I East. c. Heat-altered handaxe from Area I East.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections 1–7, comprising all Supplementary Figs, Tables and a guide to the Supplementary Information.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Davis, R., Hatch, M., Hoare, S. et al. Earliest evidence of making fire. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09855-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09855-6